Cartoonist Batton Lash was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York, where he attended James Madison High School. He went on to study cartooning and graphic arts at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan, where his instructors included Will Eisner and Harvey Kurtzman.

After graduating he took on various art-related jobs, including doing pasteups for an ad agency and being comic book artist Howard Chaykin’s first assistant. As a freelance illustrator, Lash did drawings for Garbage magazine, a children’s workbook, the book Rock ‘n’ Roll Confidential, the Murder to Go participatory theater group, a reconstructive surgery firm, and other projects. For several years he shared a studio at 225 Lafayette Street (former home of EC Comics) with comic book inker Bob Smith.

In 1979 Brooklyn Paper Publications asked him to create a comic strip and Lash came up with “Wolff & Byrd, Counselors of the Macabre,” which ran in The Brooklyn Paper until 1996 and in The National Law Journal from 1983 to 1997. He also did editorial cartoons for The Brooklyn Paper off and on for a 12-year period, did courtroom graphics for two cases, and prepared charts for The New York Daily News advertising department for sales meetings and in-house presentations.

In the 1980s and early 1990s Lash drew W&B stories for such publications as TSR’s Polyhedron, American Fantasy, and Monster Scene. Original Wolff & Byrd stories have also appeared in a number of comic books, including Satan’s Six, Mr. Monster, Munden’s Bar, Frankie’s Frightmare, Crack-a-Boom, The Big Bigfoot Book, and Panorama. Starting in May 1994, Wolff & Byrd held court in their own bimonthly comic book, Supernatural Law, from Exhibit A Press, which Lash established with his wife, Jackie Estrada. Exhibit A has published more than 50 comics, including several specials featuring Wolff & Byrd’s secretary, Mavis, as well as numerous deluxe trade paperbacks collecting the comic book series. Wolff & Byrd also appear in Lash’s online version of the series at SupernaturalLaw.com.

Lash’s non-W&B work includes art for Hamilton Comics’ short-lived horror line (Grave Tales, Dread of Night, etc.); The Big Book of Death, The Big Book of Weirdos, The Big Book of Urban Legends, and The Big Book of Thugs for Paradox Press; and Aesop’s Desecrated Fables for Rip Off Press. He is also co-wrote The Penguin’s Putdowns (a book of riddles, for Warner Books), and wrote the notorious Archie Meets The Punisher, the 1994 crossover between Archie Comics and Marvel Comics. He also wrote a 3-part Archie story, “The House of Riverdale,” in the fall of 1995. Most recently, he wrote two Archie Freshman Year miniseries for Archie. Batton has also written numerous Radioactive Man stories for Bongo Comics. His most recent non-W&B project was “The First Gentleman of the Apocalypse,” an online series published via Aces Weekly.

Batton was discovered to have a brain tumor in the fall of 2016. Treatment included surgery, chemo, and radiation, and he continued to write and draw his comics and appear at conventions and other events. The cancer came back aggressively in late 2018, and Batton passed away on January 12, 2019.

Jackie Estrada

Jackie Estrada wears many hats: convention organizer, book editor, co-publisher of Exhibit A Press, and administrator of the Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards.

A San Diego resident since the 1950s, Jackie got involved in helping to put on the San Diego Comic-Con (now called Comic-Con International: San Diego) in the mid-1970s (and she has attended every SDCC). In addition to having edited nine of the Con’s program books over the years, she helped start the Robert A. Heinlein annual blood drive, created the position of pro liaison, and created (and was the first coordinator of) Artists’ Alley at Comic-Con. She has been administrator of the Eisner Awards (the “Oscars” of the comics industry) since 1990, and she chairs the Con’s guest committee and awards committee.

With husband Batton Lash, Jackie co-founded Exhibit A Press in 1994 to publish Lash’s comic book, Wolff & Byrd, Counselors of the Macabre (now Supernatual Law). Jackie edits all of the company’s comics and books, does the lettering , and handles the public relations.

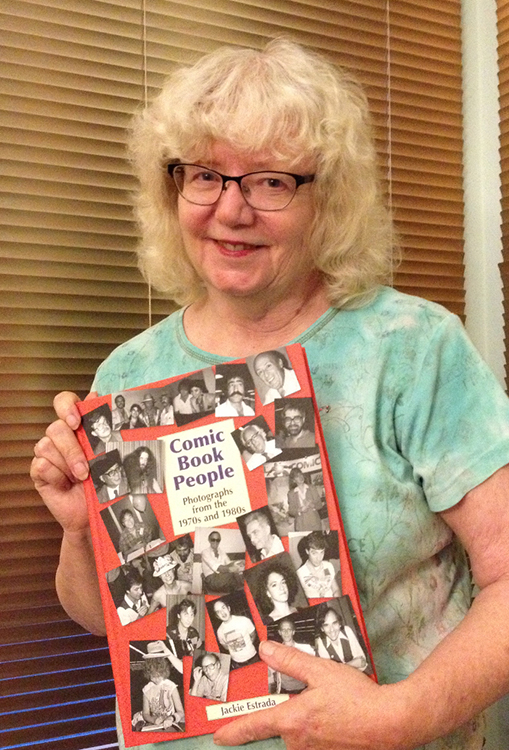

Since the mid-1970s Jackie has been taking photographs at comic conventions and related events around the country, and the photos have been published in a number of books, post notably Dark Horse’s Comics: Between the Panels and the coffeetable book Comic Con: 40 Years of Artists, Writers, Fans, And Friends. Her own book of photos Comic Book People: Photographs from the 1970s and 1980s was published by Exhibit A in September 2014.

Counselor for the Counselors of the Macabre

by Batton Lash

Probably the most asked question I get at conventions, in interviews, and at store signings is “Are you a lawyer?” My reply is to paraphrase that old Robert Young commercial, “I’m not a lawyer — but I draw them for comics.”

The Origins of W&B

Let me bring the uninitiated up to speed: Back in 1979 I had an opportunity to do a comic strip for a weekly newspaper in Brooklyn, NY called, appropriately enough, The Brooklyn Paper. The publication originated in downtown Brooklyn, the hub of the borough. (At one time Brooklyn was considered a city — the fourth largest city in America. But that’s another story.) The Brooklyn Paper was a free paper distributed to all merchants and offices in and around the downtown area: Brooklyn Heights, Carroll Gardens, Cobble Hill, and, most prominently, Court Street. On Court Street you had — you guessed it — the courts. And lawyers. More law firms side by side, building after building, than you could ever imagine.

So my thinking was that if I did a strip about lawyers, the main readership of The Brooklyn Paper would at least take a look, just to see what a comic strip featuring attorneys would be all about. At the time (I was only 25!), I knew nothing about the law. I didn’t even know the difference between civil and criminal law. the only thing I knew was that in most cases lawyers defended people in court. I thought that if there was a small law firm nestled somewhere in one of those gothic prewar buildings on Court Street that specialized in representing monsters and clients with supernatural problems, it would be funny — and visually interesting.

So on September 19, 1979, the first episode of Wolff & Byrd, Counselors of the Macabre (subtitled “offbeat courtroom drama” — did I want to grab those readers or what?) appeared in The Brooklyn Paper. The story was about a pilot who had died in 1919 and whose ghost plane was haunting Brooklyn, in eternal search for an airfield. And it was probably the most inaccurate courtroom “drama” ever to appear — offbeat notwithstanding. Fortunately for me, the attorneys to whom I was aiming the strip were extremely kind, allowing me many liberties that would never hold up in court.

I had guessed correctly — the attorneys who read it got a kick out of seeing a strip about lawyers. However, I knew the strip could be better if there was a verisimilitude to the stories. So I started going to the courts (I lived in Brooklyn Heights at the time). I sat in on ever possible trial that I could. I took notes, watched the exchange between judges, attorneys, clerks, etc. To the nonlawyer (and a country weaned on L.A. Law, Law and Order, and even good old Perry Mason), things in real courtrooms tend to be very dry… and slooooww. (I think the most exciting thing I saw was a judge tell a lawyer to be quiet and take a seat. I should add that in 1980 I did courtroom sketches at one of the John Gotti trials in federal court — that was probably the most “exciting” if only for the notoriety of the defendants.)

I started reading books about the law, and several books about famous trials. But I still felt one had to be a lawyer to really know the ins and outs, the minutiae and the unique jargon within the legal profession.

My Lawyer, Folks

Okay, let’s move ahead a few years: In 1981, I was contacted by the editor at The National Law Journal about running the strip there. I was thrilled, since that would mean a national audience — but I was also a little intimidated since that audience would most definitely all be lawyers. At this point I had made friends with some real-honest-to-gosh attorneys, who were more than willing to help with the research. The one snag was that none of them were really familiar with the comics medium. I remember one incident where I just took the gist of the information my attorney friend had provided to use it as a gag, and she was very upset, saying that the entire case she cited should’ve been in the dialogue. (I always laugh when people tell me W&B is “wordy” — they don’t know how dense it could really get!)

Anyway, the above is all a prelude to get to this essay’s main objective, which is to say how much I appreciate and rely on my legal consultant of the past eight years, Mitch Berger.

Actually, I’ve known Mitch since my college years. He also attended the School of Visual Arts, but at that time he was taking photography courses. That was 1974-76. Imagine my surprise when I saw him next — at the 1989 San Diego Comic Convention. Not only was he the publisher of an editorial cartoon magazine called Bullseye, but he had obtained a law degree and was a practicing attorney. (I never did find out what happened to Mitch’s photography career.) Mitch told me that some of his clients were cartoonists and that he helped them with publishing deals, entertainment law, advice, and (Mitch’s specialty) kibitzing. Mitch is also a lifelong comics reader. So after our “reunion” at the ’89 San Diego con, we kept in touch (we both still lived in New York). Whenever we would get together, I would show him the storyline I was working on, and without batting an eye he would help me with the research and legal jargon. And Mitch being Mitch, he would also kibitz and offer some gags.

How We Work Together

These days, with me in San Diego and Mitch in Washington, D.C., we’ve worked out a system for Mitch to “fact check” the stories.

This is what usually happens: I write a two- or three-page outline of an upcoming storyline. When there are legal points that mystify me, I’ll add footnotes asking Mitch whether such a situation/resolution is possible. I’ll also ask whether an official institution is properly identified, as well as the correct titles of attorneys, judges, and miscellaneous bureaucrats who may be involved in whatever the istory demands. Then, one of us will call the other to discuss the “case — with me taking notes. Mitch will often say something that triggers a new plot point I hadn’t thought of, and sometimes he’ll tell an anecdote about lawyers that will inspire a future story.

When I’m satisfied that the story is now “plausible” in terms of the legal system, I write the script. While I’m writing, I’ll consult the “library” of law books I’ve accumulated over the years, including everything from textbooks to trial accounts, attorneys’ memoirs, and even flash cards to get a “feel” for the law. Two places I do not go to for research are legal-oriented novels and courtroom dramas. A writer takes liberties with real-world institutions to move the plot along, so I’d much rather draw the information from nonfiction sources.

When I’ve written my final script, I run it past Mitch. He looks everything over and tells me what’s inaccurate, verifies the wording I’ve gotten right, and does more all-around kibitzing. When I get into discussions with Mitch about the legal system, he tells me to stick to cartooning. Which is fine, since when Mitch offers jokes and puns, I tell him to stick to lawyering. (Sorry, Mitch!)

So, the American Bar Association can relax; I’m not a lawyer but I do rely on a licensed attorney for my information. I appreciate Mitch’s input quite a bit, and I really enjoy bouncing a new story off him, discussing the comics industry with him, listening to his legal war stories, and just talking about life in general. And after all these years, I think Mitch is impressed that I now know the difference between a civil and a criminal case.